Shocks and structural issues for African food production; how to continue?

FoodFIRST organized a Vijverberg session on 29 August 2022, in response to the current African food security concerns, particularly the effects of rising food and fertilizer prices since the war in Ukraine - “This war will claim more lives from hunger in Africa than from violence in Ukraine,” was the title of Prem Bindraban's opinion piece of 19 April 2022 in the Dutch newspaper Trouw. It is estimated that food production in Africa could decline by at least a third as a result of the skyrocketing costs of raw materials and the scarcity of fertilizers, caused by the disappearance of producers in Russia and Ukraine. According to Prem Bindraban of the International Fertilizer Development Center (IFDC), this is a wake-up call regarding the need for a rapid increase in African food production and the promotion of soil health through the efficient use of fertilizers, which is currently extremely limited in the majority of African countries. Jan Willem Molenaar of AidEnvironment highlighted in his presentation that, in light of the escalating food crises, it is absolutely crucial to maintain a long-term perspective on African agriculture and to focus on the key elements of complex systems, such as landscape, markets, and governance, as well as the root causes of poor performance from a systemic perspective. Molenaar presented the essential components for sustainable sector transformation and how to achieve them through the development of coordinated and inclusive processes.

Key takeaways and Policy-Relevant Insights

This Vijverberg session was more of a deep dive, with participants gathered around a table to engage in insightful conversation and provide important input. Participants in this session came from a wide range of sectors and specialties, with the majority having an NGO or academic background. During this session, various policy-relevant insights emerged from the speakers' dialogue with the participants:

- Fertilizers play a crucial role in reaching food security and achieving numerous SDGs, and they should not be demonized as is done in the Western narrative. Fertilizers are not used excessively, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, and there is even a fertilizer shortage due to soaring global prices.

- One of the opportunities for the development of agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa includes soil health, which cannot be improved without the addition of fertilizers. The African Union announced in February 2022 that it would host an Africa Fertilizer and Soil Summit II for 2023, as well as develop a Soils Initiative for Africa and an African Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan.

- To advance African agriculture and assure stakeholder engagement - locally, nationally, and internationally – there is a need for speeding the learning curve of optimal fertilizer use.

- A long-term perspective is required for fertilizer utilization efficiency. This necessitates the development of innovative fertilizer solutions with minimal environmental impact. The UN should advocate for the long-term usage of fertilizers, as well as support the long-term increase in Sub-Saharan Africa, and work with the private sector to invest in true fertilizer innovation.

- To address root causes within systems, a coordinated and inclusive process is required, with three steps that include key stakeholder engagement and building local ownership along the way: 1) understanding sector diagnostics, 2) establishing a shared vision and strategy with stakeholders, and 3) a process of monitoring sector transformation as a foundation for learning, continuous improvement, and, most importantly, adaptive management.

- A sustainable sector transformation approach includes a long-term vision, which necessitates predictable and sustained funding from donors, as well as long-term engagement and flexibility in targets, plans, and budgets, backed up by monitoring and evaluation.

- Sector transformation must be conducted with urgency. This is especially true when it comes to efforts to align mindsets and visions, which can be accomplished through smaller projects with shorter time frames but all working towards a greater goal. The objective is for stakeholders to become connected with each other, establish trust, and demonstrate that collaboration is possible, as well as that the other party is not merely a stakeholder. Communication, overcoming obstacles, creating win-win situations, maintaining momentum, maintaining a sense of urgency, and having a shared vision are additional crucial factors.

- The sector transformation approach can be applied not only to developing countries but also to the EU or the Netherlands. For example, when it comes to the agricultural sector transformation in the Netherlands and the nitrogen problem, communicating this to the Dutch government can be a critical step.

At the end of the session, the moderator asked the speakers to share with the participants what they have learned from one another and from this session’s dialogue. Molenaar has learned the significance of fertilizers for soil health and feeding the world; he recommended that Bindabran should begin his presentation with a slide stating that fertilizers have a significant impact on nearly everything and are crucial to achieving the SDGs. Furthermore, Molenaar suggested that it is critical to begin by describing the type of agriculture we should envision (ideally) and then continue to argue that fertilizers play an important role in it. Bindraban stated that he understood the necessity of the various elements of an improved coordinated and inclusive process, such as establishing trust and fostering local ownership. Bindraban came up with the solution of creating a soil map with the help of the various local stakeholders. This can be viewed as a short intervention exercise, but this small victory can yield significant results in terms of building trust among all stakeholders and in the programme itself, as well as enhancing programme ownership. Bindraban and Molenaar both want to see if they can move forward together and hope to connect with Dutch Ministries on the subject.

Report

Presentation Bindraban

Dr. Ir. Prem Bindraban, IFDC was the first speaker at this Vijverberg session. Bindraban is creating a global research network to develop and manufacture Innovative Fertilizers and Application Technologies to improve crop yield and food quality while minimizing environmental effects. Bindabran started his presentation with the statement that the development of fertilizer products will improve soil health and plant nutrition, and is a critical step in "building agriculture from the ground up." Regarding the use of fertilizer in the African continent, these are rather small volumes. In a number of African nations, the import of fertilizers is insufficient to meet the demand. Bindraban argued that this reduced fertilizer use can have a significant influence on people's food security; just 1.5 to 2 million tons less fertilizer will result in output losses of approximately 30 million tons of grains, resulting in 60 to 90 million fewer people being fed. There are mitigating measures, such as the African Development Bank's May 2022 approval of the $1.5 billion African Emergency Food Production Facility, which will offer certified seeds, fertilizer, and extension services to 20 million farmers. Bindraban underlined further that mineral fertilizer use is intrinsically tied to the attainment of nearly all SDGs; providing plants with concentrated, steady, and easily accessible nutrients is crucial for their growth, health, and climate stress resistance. Nitrogen, for instance, facilitated the transition from agrarian to industrial and service-based societies; in other words, fertilizer remade global agriculture and, with it, human society. This linkage between fertilizer use and SDGs is currently being further highlighted by the ar in Ukraine.

Bindraban also referred to the scenario in Sri Lanka, which was essentially a countrywide organic agriculture experiment. In his 2019 election campaign, Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa pledged to transition the country's farmers to organic agriculture over a 10-year period. The importation and use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides were prohibited in April 2021, and the country's 2 million farmers were required to adapt to organic farming. The decline in domestic rice production was 20 percent in the first six months. Long self-sufficient in rice production, Sri Lanka has been compelled to import rice worth $450 million as domestic costs for this staple of the national diet has increased by around 50 percent. It is also anticipated that the decline in tea production alone will result in economic losses of $425 million. Although the prohibition was rescinded in response to widespread demonstrations, just a trickle of chemical fertilizers reached fields, which will certainly result in a fall in yields across the nation. The human cost has been far higher. Prior to the advent of the pandemic, the nation had proudly attained upper-middle-income status. Today, 500,000 individuals have fallen back into poverty. Sri Lankans have been compelled to reduce their food and fuel purchases due to soaring inflation and a quickly deteriorating currency. The lesson here is that science will always prevail as farming is, at its core, a rather simple thermodynamic operation.

According to Bindraban, it is crucial to note that there are no instances of excessive fertilizer use in Sub-Saharan Africa; It is used very sparingly in comparison to the West and China. Fertilizers are not evil, contrary to the Western narrative, and this should not be propagated on the African continent. To improve soil quality, fertilizers are needed. Consider both a more efficient and sustainable use of fertilizer and the fertilizer components themselves. There is currently little fertilization synergy due to inefficient fertilization. Bindraban supports Soil Health Links by introducing fertilizers into soil health systems. The IFDC supports this initiative and will make broad recommendations for the upcoming AU Summit.

In his presentation, Bindraban briefly presented the FERARI-research he is supervising. FERARI is a multi-stakeholder platform in Ghana bringing implementation and research together. It encourages public-private partnerships for the development of fertilizer value chain actors in order to provide farmers with adequate fertilizers, ultimately improving food and nutrition security. On-the-ground implementation activities will integrate scientific evidence from transdisciplinary research.

Prem's closing remarks emphasized the fact that fertilizer-based food feeds more than half of humanity. Fertilizer rejection will exacerbate hunger and poverty (do not throw away the child with the bathwater). Furthermore, agro-ecology and organic agriculture (those rejecting fertilizers) are socioeconomic and institutional forces in (excessively) food secure developed nations and are against global fertilizer use based on their excessive overuse, however, there is no case of overuse on the African continent and basic physical/biological processes on Earth should be taken into account. Mineral fertilizers will feed the planet while also reducing land clearance and preventing the loss of biodiversity. When utilized excessively, then they contribute to biodiversity loss, dead zones, and climate change; but that would be for economic rather than ecological optimization of production systems. Bindraban presented opportunities for Sub-Saharan Africa, including soil health, which cannot be improved without the addition of fertilizers, as well as innovative fertilizer solutions with a significantly lower environmental imprint. The UN should advocate for the long-term usage of fertilizers, as well as support the long-term increase in Sub-Saharan Africa, and work with the private sector to invest in true fertilizer innovation. To advance African agriculture and assure stakeholder engagement - locally, nationally, and internationally – there is a need for speeding the learning curve of optimal fertilizer use.

Following Bindraban's presentation, there was a brief round of Q&A focused on the specific data and figures presented in his PowerPoint. There were also discussions about how to move agricultural industries forward; one participant mentioned that it is still seen as a dinosaur in some ways, with the same methods of processing and products. It is also necessary to recognize farmers as agents of change and to understand that fertilizers are made from chemical elements; it is, therefore, necessary to reason from the physiology of a plant and the specific geographical context. There are currently many initiatives to reduce measures that can overstep the boundaries of the planet, such as less meat, fertilizers, pesticides, and so on, but Bindraban argued that you must do all of these measures to return to the planet's safe operating space, but there is not enough attention to change the product itself. So more funding, for example for innovative fertilizer development, is required. Ecology is a fact, but the economy is flexible.

Presentation Molenaar

Next, was the presentation of Jan Willem Molenaar of AidEnvironment. During his presentation, Molenaar focused on a long-term agricultural sector transformation addressing structural weaknesses. Structural weaknesses continue to undermine the performance of agriculture and value chains and the potential for sustainable and inclusive production and these structural weakness are currently not being adequately addressed in many programmes. Often many projects are islands of success in a sea that is polluted that will eventually engulf the islets. Examples of structural weaknesses include production volatility, weak organization of small-scale producers, commodity price volatility, poor service provision, informal trade, elite capture and rent-seeking. Achieving large-scale and sustained impact requires, at least, these four components: 1) long-term vision; 2) a systems approach; 3) addressing root cause; and 4) a coordinated and inclusive process. Figuring out all of the interconnecting elements amongst these components is a puzzle.

First of all, it is important to establish a long-term vision; what is it that you want to achieve? For instance, what does the future of sustainable agriculture methods look like, and what aspects or initiatives are necessary to achieve this? Other considerations that could guide the formulation of this long-term vision include the sort of farmers we desire in the future; it is essential that future farmers can support the country in one way or another. However, what types of marketplaces should subsequently be implemented? What are the tradeoffs between competitiveness, sustainability, and resilience, and what kind of equilibrium is required? What are the functions of fertilizers and other inputs? And what prerequisites must be accomplished for the vision to become a reality? All these questions need to be taken into account when establishing a long-term vision.

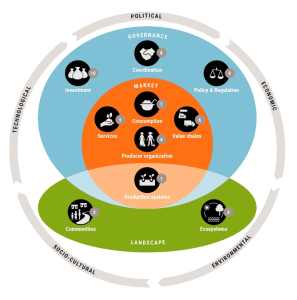

Due to the interconnection of everything, it is imperative to apply a systems-based approach; looking at the explicit (or tangible) and implicit (or intangible) root causes of the structural weaknesses, or systemic issues, in and between the system components. They correspond to a great extent to what has been identified as conditions for systems change. Nonetheless, it might be difficult to know where to start. In their report on Sector Transformation, Jan Willem Molenaar and his colleague Jan Joost Kessler identify three spaces of a systems-based approach, namely: 1) the landscape space, which entails production systems (its viability, sustainability and resilience), as well as its relationship with the surrounding communities and ecosystems, such as basic services & infrastructure, natural resource management and local norms and values; 2) the market space, which entails how farmers organize themselves in relation with each other and to others, such as producers, service providers, value chains and consumers, and to what extent these markets are workable, feasible, and scalable. What type of value or supply chain are you constructing, and what are the underlying rules? In addition, more attention must be paid to a livable income - it can be necessary that the market and consumers bridge this gap; and 3) the governance space, which refers to the policy and regulatory environment, such as inputs (e.g. licensing, quality, subsidies), market management, and land tenure, as well as the capability of the sector to collect revenue and re-invest it in a strategic manner (investor attractiveness). It also requires coordination, information sharing with farmers and stakeholder alignment.

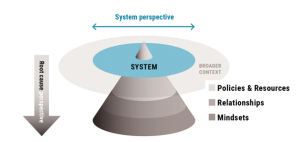

The three levels of root causes of underperformance that need to be addressed for transformative change are presented in the diagram below.

A coordinated and inclusive process is required to address these root causes. This has three components to consider: 1) sector diagnostics, which is concerned with developing a shared understanding of the system dynamics, context, and root causes of underperformance; 2) vision and strategy development, which involves developing a shared vision with the key stakeholders involved and agreeing on an effective strategy; and 3) and managing for transformation, which refers to understanding the various factors involved and thus coordinating and steering the process in the right direction. It is critical to comprehend such factors as participation, goal-setting, the value of small victories, stakeholder trust, and so on. Molenaar emphasized the importance of local ownership for a coordinated and inclusive process, saying that it is where it should begin and end. Then, as previously stated, there must be a vision, preferably a long-term vision or a horizon of where it should be heading with the key stakeholders involved. Effective strategies are vision-oriented, integrated (e.g., they address the connections between system components and root causes), and truly transformative in that they address the three levels of root causes (policies & research, relationships and mindsets) for the identified systemic issues. Then, using an integrated system perspective, root causes can be addressed alongside the three spaces of landscape, markets, and governance. There will always be a need to strike a balance between short-term gains and long-term outcomes. There must also be room for continuous learning, so this approach and management must be flexible and adaptable, particularly to its changing context; as a result, predictable and sustained financing is required. Implications for donors include preparing for long-term engagement and allowing for flexibility in targets, plans, and budgets, backed up by monitoring and evaluation (mixed methods). Finally, this would necessitate a true partnership, complementing other development actors, so that by understanding your own place in the system and the systemic buttons you can push, as well as the interdependence within the system, a more balanced, coordinated and inclusive process could be established, always from a root causes perspective and taking into account the broader context.

Discussion

Following the presentation, there was time for a Q&A and dialogue with the participants. The dialogue centered on a crucial aspect, bringing together the presentations by Bindabran and Molenaar: what role do fertilizers play in sustained sector transformation and what are the underlying causes that impede effective fertilizer use?

Participants raised a number of important points, including that one of the major layers of root causes is still the post-colonial narrative, which continues to have consequences. Another layer that a participant mentioned is the overly dependent relationship that farmers have with other actors and the need to appease them. One made the remark that the responsibility of ensuring sustainable food supply is often put on the farmers, but there is an insufficient discussion regarding the other actors in the supply chain, such as consumers, traders, markets and grocery stores; therefore, an appeal should be made to all actors, they all need to be involved when talking about sector transformation.

Furthermore, the application of change theories can be a valuable tool for establishing leadership, vision, and so on. To achieve this, coalitions of committed key stakeholders who are willing to change and effect change must be established. Another participant mentioned that when it comes to key stakeholders, some are frequently left out of the conversation, whereas in terms of global systems, large corporations and multinationals have an incredibly large share and impact, generating more revenue than the GDP of certain countries. If you do not include them, the dialogue is incomplete. It is essential to consider these giant businesses, their roles in the system, and the extent to which local ownership can be achieved.

Another participant argued that stronger coordination based on national policy is needed and that each country has its own projects, but there is little to no coordination between projects, actors and countries. The Netherlands frequently provides budget support, but this does not work because governments lack the capacity to distribute the funds. How do you incorporate these concerns into the Molenaar sector transformation story? A great number of actors are active in two of the 10 components as mentioned in the presentation of Molenaar, and then, beyond the policy level, they should connect with actors who are active in other components, in that way there is attention to the complexity and mutual relationships.

Many participants agreed with the crucial importance of sector transformation, especially in terms of local or national ownership. There need to be a vision and agenda in place, at the moment many actors are not given the opportunity to take ownership of themselves. According to a participant, there is too much focus on the opinion of external markets and visions, such as cash crops and the Western narrative on fertilizer usage.

Sector transformation need to have a sense of urgency. At last, multiple participants mentioned that mindsets and creating shared visions are extremely important, and this can be accomplished through smaller projects with shorter time frames. The goal is to get to know each other, build trust, and demonstrate that collaboration is possible, as well as that the other party is not merely another stakeholder. The FERARI-programme of Prem Bindabran was used to put the theoretical concepts of Molenaar's presentation into practice, such as how to engage the various stakeholders to conceive a shared long-term vision and the challenges that Bindraban is facing. The participants raised some critical specific points that Prem can incorporate into its FERARI-programme. For example, in terms of small victories and local ownership, it is critical that Ghanaian stakeholders fund the program in part themselves, not only for local ownership but also for ensuring continuous engagement and responsibility. Other important elements that were identified by the participants were improving communication, overcoming obstacles, creating win-win situations, maintaining momentum, maintaining a sense of urgency, and having a shared vision.