[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Urban food systems and the value chain

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]

Opportunities for urban food systems, René van Veenhuizen (Ruaf)

The world is urbanizing, people move to cities, not only to the big urban agglomerations, but also to the rural towns. People have wider access to information and are developing different lifestyles. ‘Foodwise’, people are net consumers. Food systems are vulnerable and people have less access to nutritious food. Diet related illnesses are spreading, food waste is growing, and these trends are exacerbated by climate change. Due to logistics, most cities have only food in stock for two days.

The complex dynamics of urban-rural development needs diversity of initiatives and policy re-orientation:

- From emphasis on increasing production as a rural issue, to include the diversity of urban and rural based production and consumption.

- Include the variety of actors, along formal and informal value chains.

- From sectoral to territorial policies, seeking synergies and enhance urban-rural linkages.

- Address a mix of drivers — economic but also social and environmental: include employment generation in the changing food system.

Resilient cities are the target of the Sustainable Development Goals. With the Milan Food Policy, cities signed to work on improved food resilience. The role of urban agriculture in urban food systems depends on many factors, among which are location and scale. Within cities 11% of irrigated land is situated, within a 20km circle this is about 60%. This is the urban setting within which people are looking for opportunities.

Urban agriculture addresses actual urban challenges:

- Growing urban poverty and social exclusion;

- Growing food insecurity and malnutrition in cities;

- Growing need to enhance resilience of the cities and reduce climate change, disaster risks, and the ecological foot print;

- Growing waste management problems;

- Growing need for green spaces and recreational services for the urban population.

It provides diversity in business opportunities for:

- -Producers – farmers and growers;

- Processors – dairies, abattoirs, fruit & vegetable preparation and packing, processed food manufacturers etc.;

- Wholesalers and distributors of all kinds of products;

- Retailers for a diversity of consumer preferences – supermarkets, independent food shops, markets, street food traders, home delivery, community bulk buying groups, etc.;

- Caterers – public sector meal provision, work canteens, eating out places, hospitality providers;

- Waste management – food waste collection and food waste disposal;

- Other (non-food system) actors.

In an urban food system, there are shorter chains where people know from where the food is coming. It can also provide other services, such as health care and tourism (‘pick your own’-farms). It will help reduces food waste, and in addition makes using waste possible. Further on, it is the place for innovative strategies, for example new technologies using led light for growing produce.

Cities actively support the transition to urban food systems:

- Creation of an enabling policy environment — issue such as recognition and formal acceptance, adapt legislation, create institutional home, integration into city planning, multi actor platforms and food policy councils;

- Reducing health and environmental risks — think off coordination, zoning, awareness creation, Active pollution Control;

- Enhancing availability and access to land and use security — Mapping, Zoning, Tax incentives, Temporary Agreements, Land banks;

- Support to Farmers and to Local value chain initiatives — facilitate access to land, finance, marketing (youth involvement, extension support, value chain development, farmers markets);

- Preferential public procurement of regional and organic products;

- Reduce food waste and losses and stimulate resource recovery and recycling.

Summing up:

A City Region Food System is a complexity of actors, flows, and relationships, related to food it can facilitate improved (territorial) urban planning and vertical and horizontal governance.

There is a need for (new) information and indicators that support the active involvement of a variety of actors in (green) value chains and policy development platforms.

Participatory (multi-actor) approaches should include formal and informal actors, to form partnerships, empower local agents and generate value and mutual trust.

There is a wide variety of opportunities for employment and SMEs in city region food systems, ranging from social or community enterprises to family businesses and larger enterprises.

Stimulation of employment for youth requires comprehensive strategies that include pro-active financial and policy support.

Technical and Business training needs to be provided for new and existing entrepreneurs, with emphasis on youth, supported by local, national and global partnerships.

Blind spots in value chain support, Yves van Leynseele (UvA)

This presentation is about inclusion and exclusion in the value chain and not particular about the city; it is rather about the variety in smallholder farmers; but these insights themselves also apply to the urban situation. At the UvA we work on an inclusive framework for the value chain which is still a central concept.

Many concepts are included in the value chain discourse. We tend to consider inclusion only in economic terms, not in political terms. Governance we frame mainly in terms of standardization. And we look at the benefits for only the poor, not for the wider well being.

Value chain collaboration is roughly public-privet partnership, mitigating inequality and other problems. It is becoming horizontal collaboration. Also the role of the state is shifting, actively creating a level playing field and taking the role of a watchdog for guidelines.

Two aspects of strategies are worth mentioning. First, going ‘beyond the chain’: mixing cash and food crop for food security, livelihood security. Thus, well-being is [art of the value chain. There is, second, a focus on entrepreneurial farmers: selecting on farmers’ business attitudes, land size, capacity to invest, new roles for producers, agro-ecological potential of a productive area, thus selecting those for support who already have a stronger position, which might be a risk for a comprehensive and inclusive chain.

There are some blind spots in the value chain collaboration

There is hostility against the middle man, those who are close to the producer. They are often seen as too informal and prone to corruption. Forgotten is that these people do have a function, standing close to the producers. Their personal relations to producers serve other important social functions (some women also accompany you to a funeral, for instance).

Outcome based or ‘tick box approach’: if this and that applies, these people need inclusion. That is too simplistic, inclusion is a process.

Farmers operate in different value chains and markets, for instance oil palm and cocoa. The focus in policy and research is on the poor as producers. There is, however, heterogeneity of farmers with different trajectories. Innovations have to follow this diversity, interventions have to be focussed on the farmers, their well-being and their capabilities, and not just cater certain groups.

Value chain collaboration is embedded in social norms and in a territorial setting. The shift from food to cash crops also has consequences for the landscape.

Challenge for value chain collaboration is inclusion of the productive farmers. Farmers who have their own land, the entrepreneurial farmers and absentee farmers (‘telephone farmers’), are now the targets. The caretaker and sharecropper farmers, those who actually often do the work, have to be included.

RAIN project, Remco Rolvink (Dasuda)

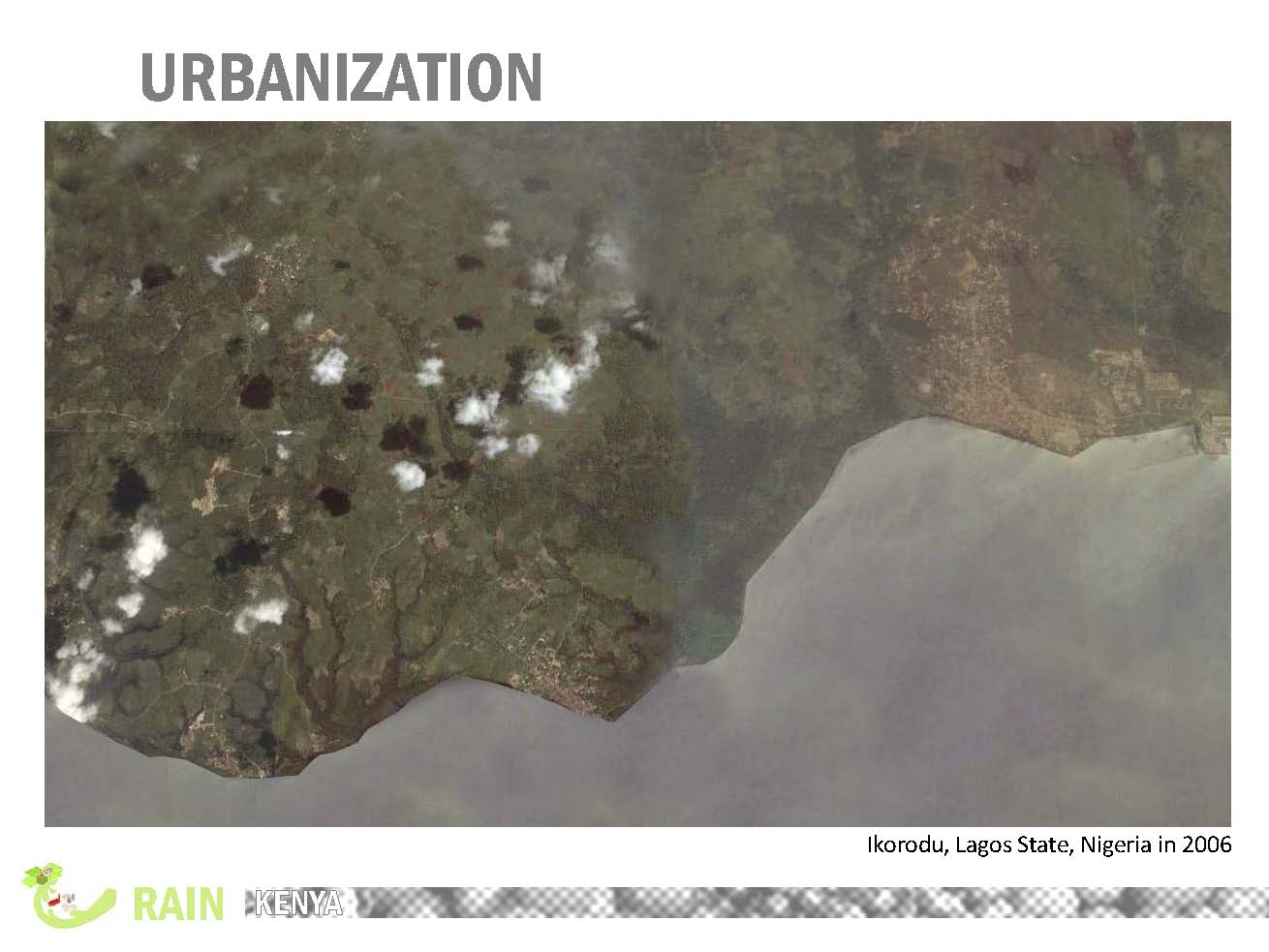

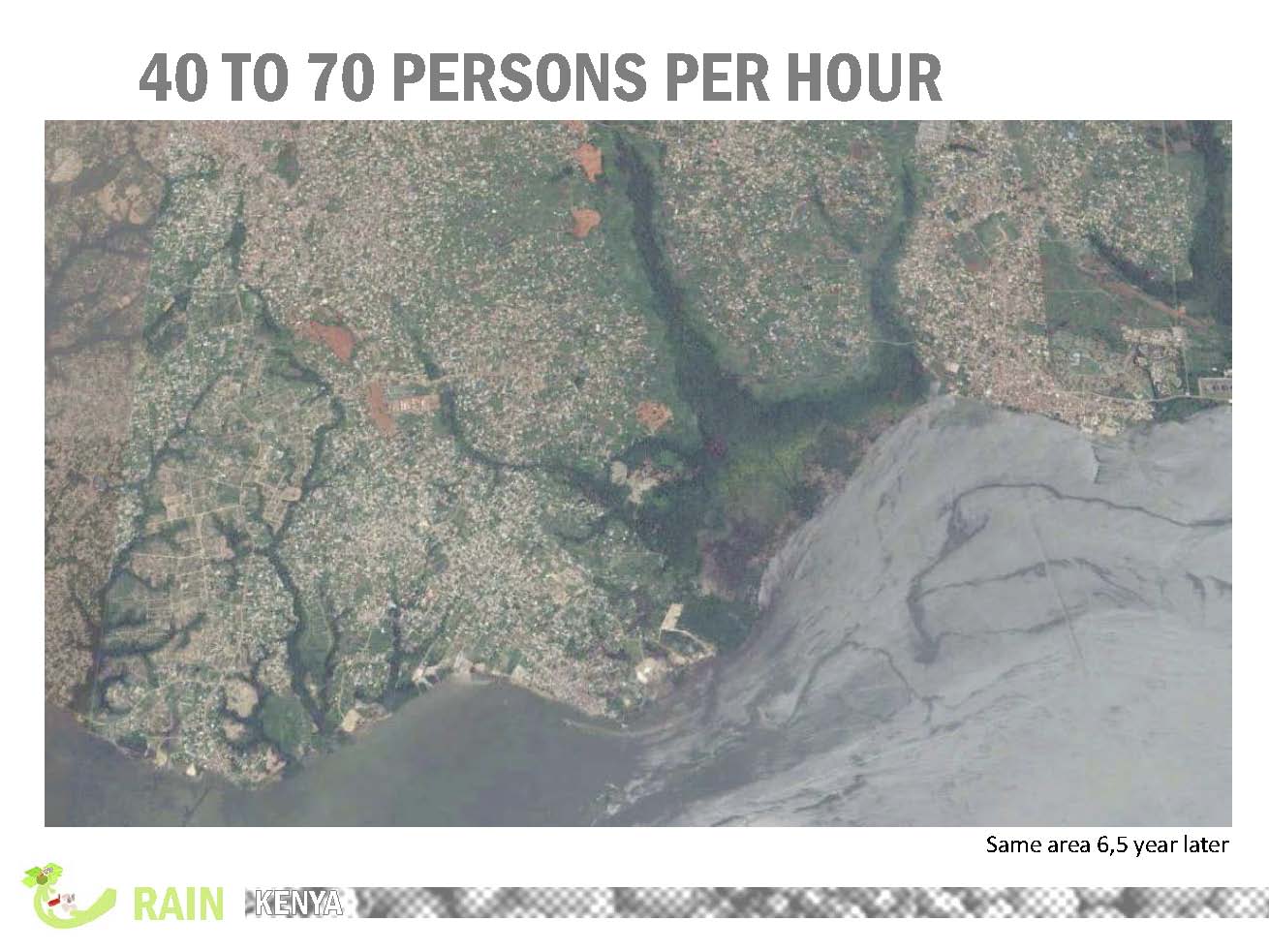

Global population growth, not only food but also housing is becoming an issue. Houses take over the land: it moves fast – in Nigeria every hour 70 persons are added to the population.

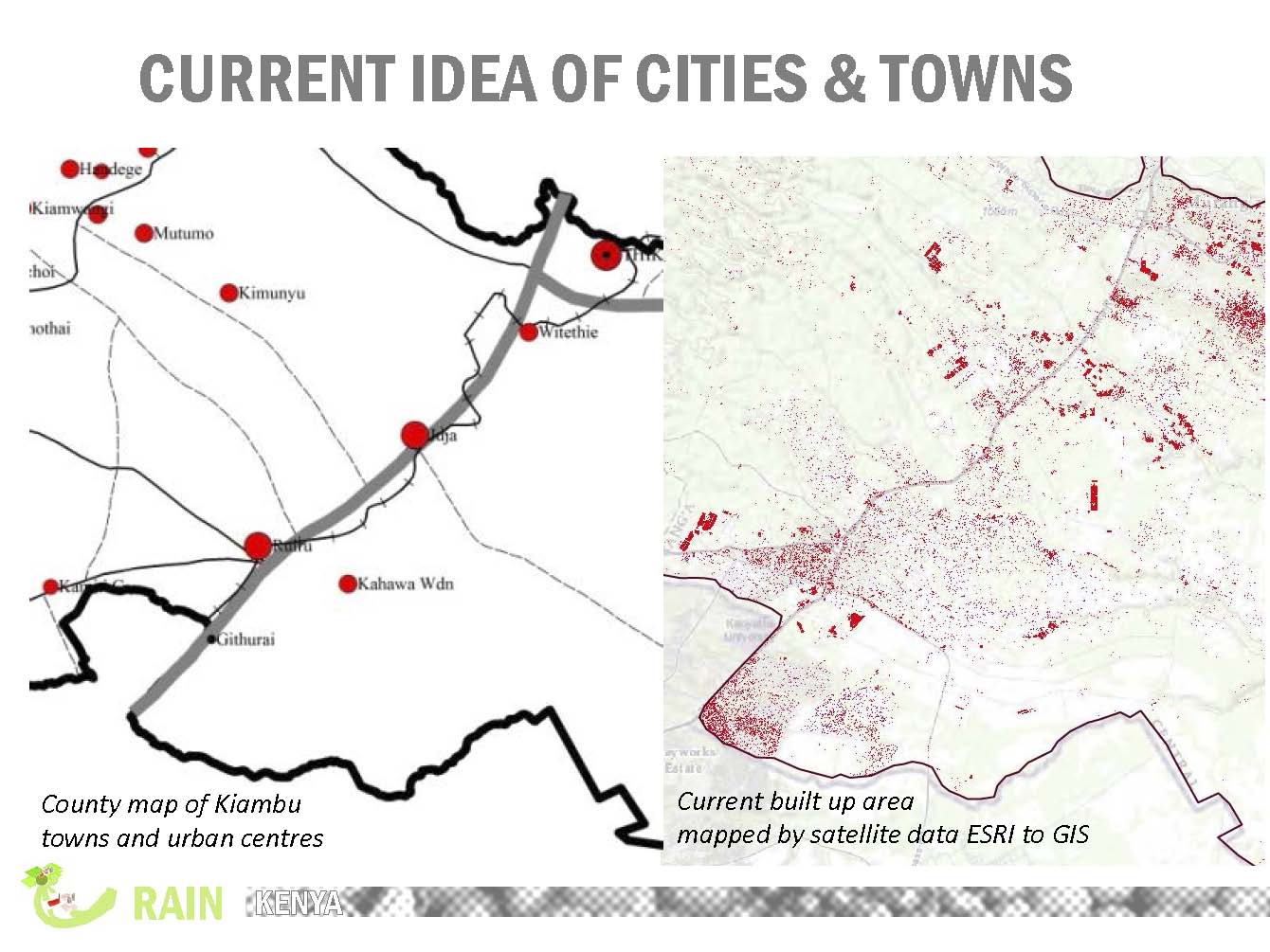

There is a discrepancy between what governments file as being build area, and the actual situation. Rural area’s in Africa are being invaded by heavy urban sprawl, turning these areas so to say into ‘rurban’ areas. An example is the Kiambu Area in Nairobi, where the Dutch government and the local county have a common project.

The sprawl pushes farmers out of the cities: land is becoming too expensive for extending farms, so they rather sell their land for better prices than what they earn with their produce, and they move the farms further away from the cities. This deteriorates the food situation for the cities: transport of food takes longer, causing more waste and higher prices, and also the loss of jobs in farming.

The sprawl pushes farmers out of the cities: land is becoming too expensive for extending farms, so they rather sell their land for better prices than what they earn with their produce, and they move the farms further away from the cities. This deteriorates the food situation for the cities: transport of food takes longer, causing more waste and higher prices, and also the loss of jobs in farming.

The RAIN project wants to bring back the production of food closer to urban areas.

Planning is a critical issue with these effects of rapid urbanization in order to fully use agricultural potentials and provide a secure situation for sustainable investments. Working along with local government is important for the necessary cross-sectoral approach to achieve effective implementation and strengthened urban-rural relationship to enhance economy and liveability.

The focus is on productive land and on processing of food in those areas. It is about spatial planning: what can or should happen in which place, where the best locations are, how the link with the infrastructure is.

Market analysis shows a number of issues:

1) Lack of a continuous and reliable supply of produce;

2) Lack of produce that is consistently high in aesthetic quality and nutrients and low in pesticides;

3) Time and financial investments required that are related to procurement;

RAIN concept of agro-hubs provide for the missing link between producers and the markets. In the case of Nairobi, the centre manages distribution, packaging, logistics, etc. Such a centre also creates jobs. Examples on which RAIN is inspired are the Greenports in the Netherlands (Venlo, etc.). The facilitating role of local governments (province or county) is very important for these centres.

Uganda Food Change Lab , Felia Boerwinkel (HIVOS)

The Objectives of the Uganda Food Change Lab are to guide choices for the growth of Fort Portal city and its rural hinterland, that work for health, jobs, urban citizens, farm households and farmland. The aim is a ‘virtuous circle’ of rural-urban local economic development.

The Food Change Lab is a social space where we move from problem to solution. The idea for the change lab is to spend dedicated time on problem analysis instead of immediately jumping to solutions: explore the issues with a wide coalition of players in the local food system. Have people co-create their understanding of the issues as well as co-creating possible solutions.

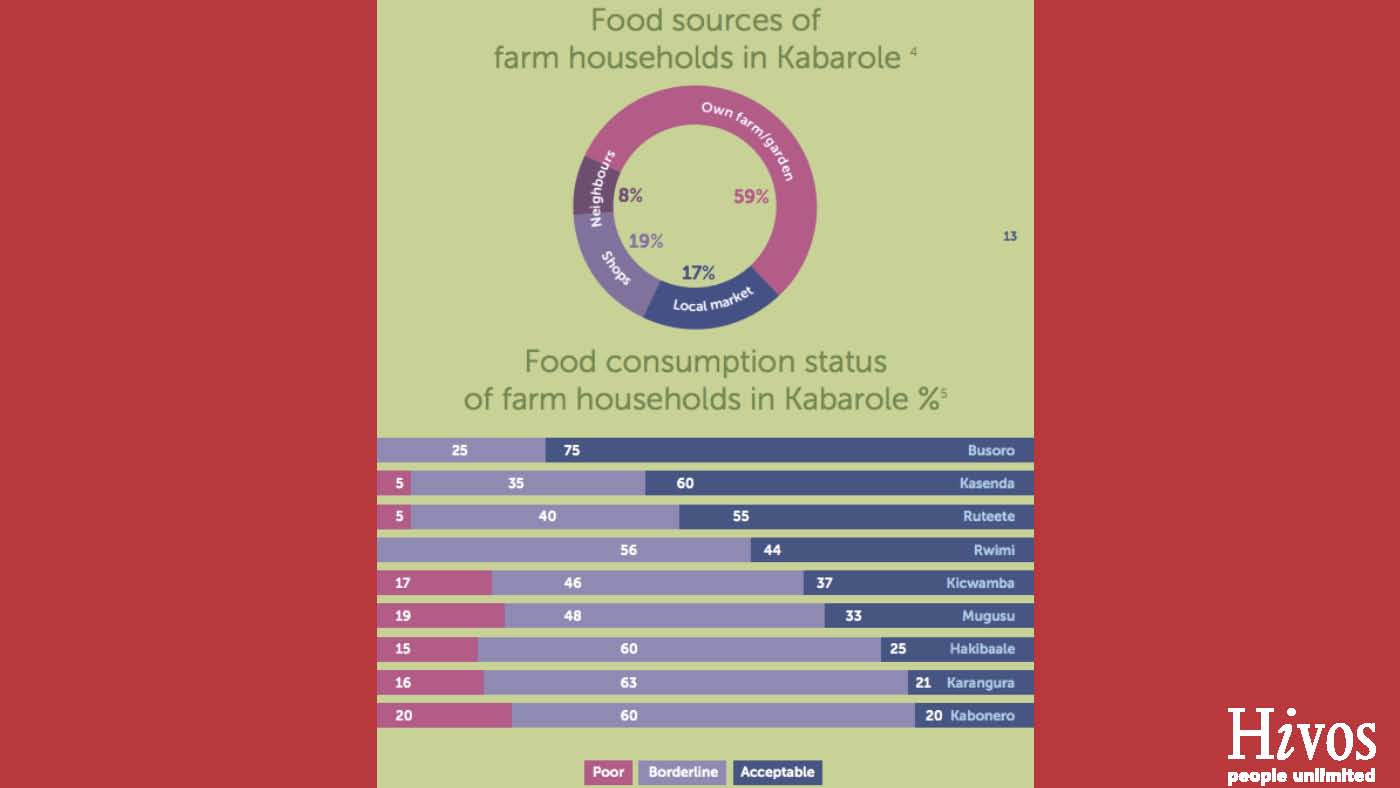

Child stunting is high in Uganda and especially high in the western region of Fort Portal town – which is strange considering the fertile region is also known as a bread basket for the country and wider East African region. To make matters more worrisome; the town is slated to grow ten-fold in the coming 25 years, but Uganda’s planning policy is overlooking explicit planning for food systems.

The Lab took these facts as a starting point to convene a wide group of actors and to start analysing the local food system. Citizen research showed that increasingly, rural people rely on the market for their own food, and not on their produce (slide). People’s diet has become poorer in nutritional value. Low-income urban dwellers increasingly rely on street food, due to lack of money as they often cannot afford the fuel to cook.

The Lab’s research found that actually, a lot of street food sold in these informal settlements is very nutritious. However, old colonial laws prohibit vending on the street, so street food vendors find themselves chased away. Thus, a potentially good and nutritious source of daily food threatens to become unavailable (Slide).

Added to this is that more and more trucks with matoke (or ‘matooke’, a local starch banana) are leaving from Fort Portal headed to Kampala, whereas processed food is brought back. There is hardly local processing, so we see a situation with very little value added and simultaneous depletion of soils. What is being done: meetings of parliamentarians on local farms brought more understanding, and now there is at least thinking about the food system. There is also growing understanding for the role of street vendors at the local government level so that some positive regulation can be installed. Lastly, the National Planning Authority has recognised the importance to explicitly plan for food systems and is now working with Hivos and local partners to incorporate this in new policy planning.

Food Change Lab publication with information on the process and content of findings can be found on http://www.foodchangelab.org/assets/2016/09/food-lab-pub.pdf .

Discussion

One cluster in the discussion was about the role of informal sector, more particular the street vendors: do we have to formalize this sector? And if yes, how? This sector plays an important role for feeding people and they belong to the urban food system. If governments do not attend their position, the food situation will deteriorate, shifting to more expensive food in supermarkets.

People have the data about the importance of the informal sector and street vendors.

There is the fear of food safety. If vendors are accountable, they will be more careful, not using contaminated water, e.g. Regulation is however not the first or only answer. People will not eat from a vendor when his or her food is contaminated – where people chose to buy their food is itself a strong mechanism. Formal regulation tends to cause more waste and leads to higher prices. So, don’t destroy a system that delivers but support it. And look at improving the food on the street by organising the use of additions that make street food more nutritious.

Another observation in the discussion is that Sub Sahara Africa is fairly hyper capitalistic. Expensive food that is also of high quality can win a big share of the market in a short time – people want quality and they like to pay for it. These market dynamics are important to keep in mind. And in South Africa, for example, elderly pensioners have good buying power and buy at the supermarkets. In rural areas, family members from the cities bring in money on occasions such as funerals, when the whole family gathers.

Lastly some other points made in the discussion. First, in Europe we all eat oranges from Spain and transport these all over the continent. Why then demand that in Africa every country produces all of the produce than is sold on the market.

Second, who is earning from the sale of land when farmers sell their land to be build on. Local authorities are very important when it comes to land use in Africa. Will there be enough land for the production of food? All the actors involved have to connect a value to the different functions of food – not only nutrition, but also greening of the economy, climate change, social inclusion, etc.

Finally a reminder: success in The Netherlands came through the connections and cooperation between education and banks, strong institutions and organisations.

Further reading:

[> Ruaf on urban food systems

[> NWO-WOTRO programme ‘Inclusive Value Chain collaboration’

[> Hivos ‘Food Change Lab’

[> Dasua ‘Rain project’[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_column_text]

foodFIRST theme 2016/17 “The African future is for young, well educated, market oriented and organized farmer-entrepreneurs” — more to this theme on: A policy paradigm for rural development cooperation in Africa, Vijverbergsession of 2 December 2015.

Rabobank, Bezuidenhoutseweg 5, Den Haag. With René van Veenhuizen (Ruaf) and Yves van Leynseele (UvA)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]